SEATTLE — For 50 years, the Center for Whale Research (CWR) has taken a yearly survey of the Southern resident orcas-- the subset of killer whales that almost exclusively live in the Puget Sound and Salish Sea, and almost exclusively eat salmon for nourishment.

For nearly that entire time, the populations have decreased as the three pods, J, K and L, have struggled to reproduce.

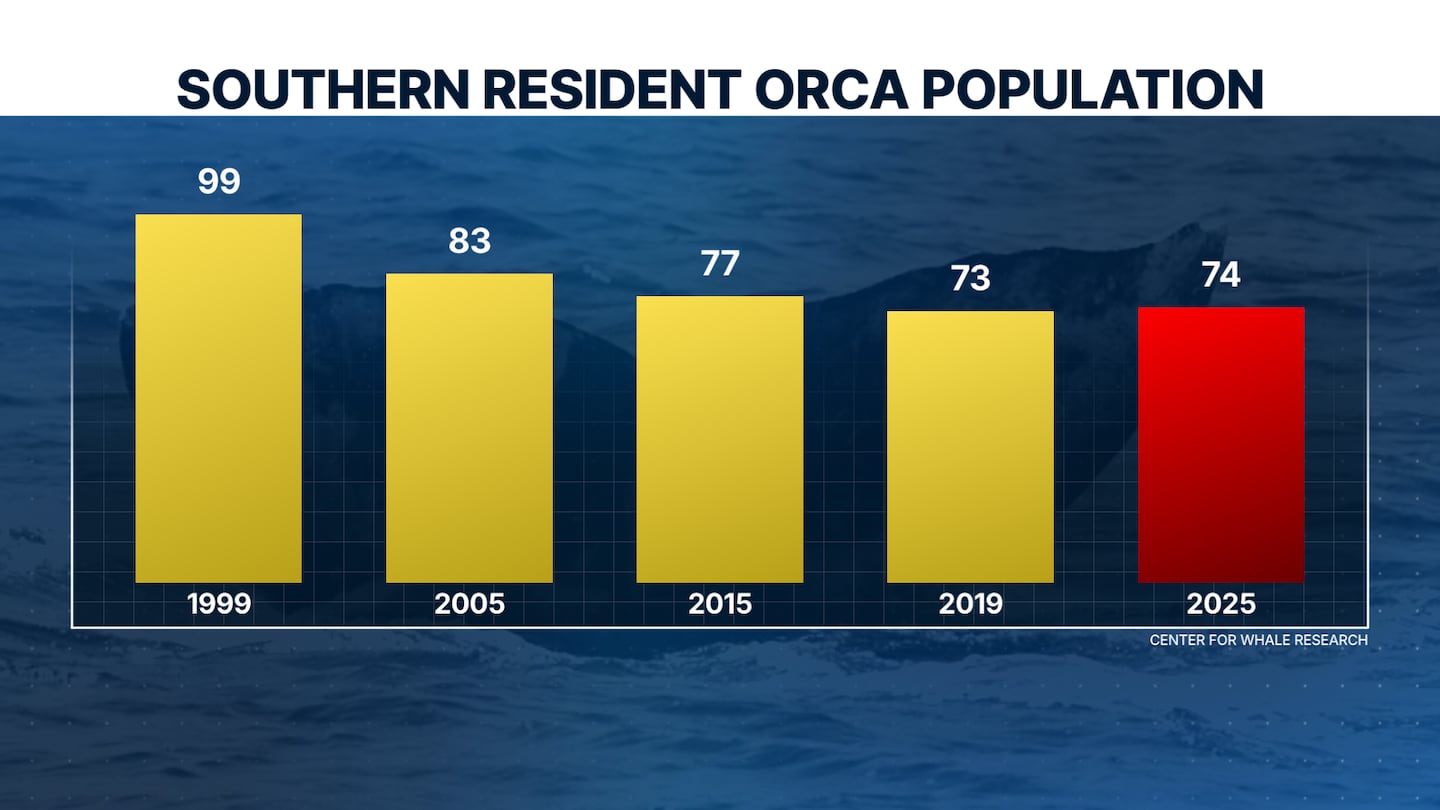

On Tuesday, CWR released new research showing many challenges still lie ahead, but there may be a shimmer of hope, as 74 orcas were counted compared to the 73 announced in 2024.

In 1999, the same survey found 99 Orca in the Puget Sound waters.

“They’re holding steady but barely. They need to increase in population,” said Howard Garrett, the founder of the Orca Network and president of CWR’s board.

Four calves were observed during the study period from July 2, 2024, to July 1, 2025.

Of them, two females in J Pod survived.

A male calf in L pod wasn’t seen past October, and a third J Pod calf was seen deceased, being carried by its mother in a “tour of grief.”

K-pod is now the smallest it has ever been recorded after its oldest male, who had sired several offspring across the three pods, has not been seen for months and is presumed dead.

“K-pod has always been problematic. They’ve been the smallest pod and they’re losing more members than they’re gaining. They had one baby a couple of years ago, but that was after 10 years of not having a single surviving offspring. They’re looking like they may be on a trajectory downward,” Garrett said.

Garrett offered similar concerns about the two youngest J pod calves, pointing out that the first few years are critical for their survival and the future of the pod.

The two calves that died in the census time offer him a clue at the problem.

“What that indicates to me is that there are at least times in the past year and a half, considering those young ones that have died, when they didn’t have enough to eat, when the mothers were stressed and went hungry for weeks or months at a time,” Garrett said.

The need to eat is two-fold, having enough nutrients to grow and develop. When a nursing or pregnant mother is hungry, her body burns the energy in her blubber.

For the Southern Resident Orcas, that can be an issue as Garrett notes-- ‘forever’ chemicals and ‘forever’ plastics have made their way into the environment and into whales’ blubber, meaning it’s passed on to calves.

“The challenge is to not let them get hungry and that means we need to have more fish out there, more Chinook salmon,” Garrett said.

The main ways to do that is by restoring the historic migration paths of salmon. Famously, salmon instinctively swim from oceans and the sound, up fresh water ways to the waters they first hatch. Protecting and undoing the damage to those waters helps ensure there is food for the orca.

“They’re barely hanging on but you know, that’s kind of hopeful because from there, if we can improve their situation, they’re staged to be able to increase their population and become more of a healthy community.”

Garrett is encouraged by the removal of dams, like the Elwa River Dam, and the creation of culverts that clear and recreate streams to allow for salmon migration, as helpful to the orca.

“There’s so much good work going on, I would suspect that they would be in worse shape now if that had not been done. It’s just not quite enough,” Garrett said.

Garrett points to the more dams that are harmful to salmon needing to be removed, as well as more restoration projects to truly reverse the trend of a dwindling orca population in the Puget Sound.

©2025 Cox Media Group